Ferris Bueller Didn't Kill OJ Simpson, but Frank Drebin Did Save the Queen

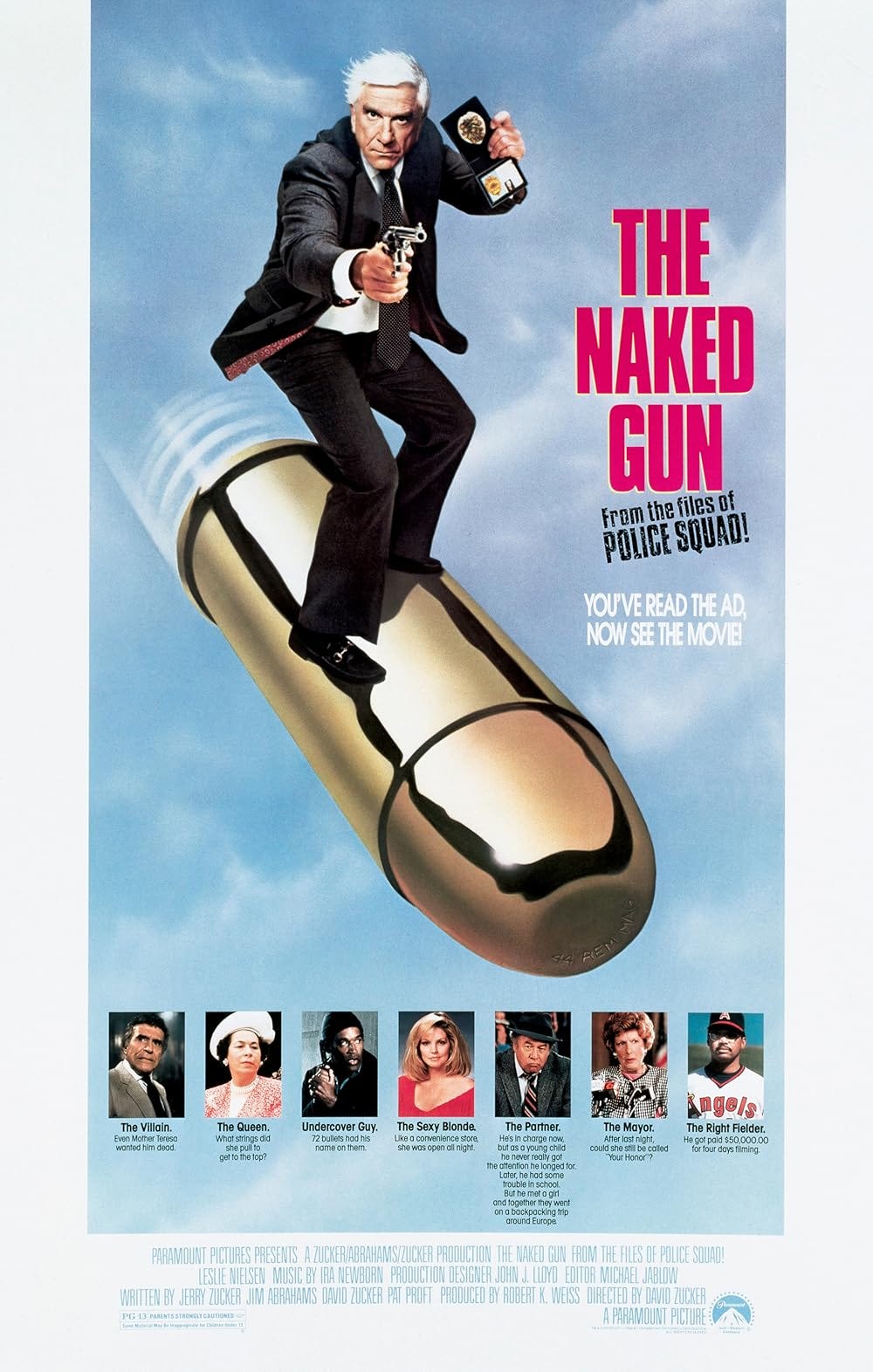

A Formalist Approach to The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! (1988)

The Naked Gun (1988) - Formalist

As Santa Claus once said, “Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.”

Actually, it was Edmund Gwenn, the jolliest little salesman in Miracle on 34th Street (1947), who allegedly said these words on his deathbed when weighing up the various challenges of his life thus far. I find it a very telling quote. Comedy is a natural talent that is deeply scrutinized and harshly judged. Something is either funny or it isn’t; the joke either lands or it lingers, hoping someone will take pity and softly chuckle it into a quiet nonexistence for the pride of the teller. Death, on the other hand, isn’t the mark of a man. Death is an unchallenged tragedy; no one deigns to judge the mode of a man’s death, unless, of course, that man is OJ Simpson and the one in question is Leslie Nielsen proclaiming that the right way to die is having your nuts bit off by a Laplander beside Simpson’s nearly-bereft wife. Santa knew that, and so did the Zucker Brothers (and Jim Abrahams) when they decided not to make a comedy at all, but rather make a very funny drama in their 1988 The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad!

This week, the Review Roulette wheel landed on Formalist as our approach to The Naked Gun, which I watched for the first time in anticipation of the legacy sequel starring Liam Neeson (out today - August 1). I’ll be seeing it in two weeks at which time I’ll find out if I was right in convincing my husband that Neeson is the perfect choice to reboot this character from films that I’d never seen and that he has loved dearly for literally longer than I have been alive. Fingers crossed! And no spoilers in the comments until then please!

So, comedy is hard. It’s hard to write, and it’s hard to act, and I’d guess it’s hard to direct. It’s super easy to criticize though. Finding the angles of entry for analyzing comedy is easy because every joke in a comedy is like a 3D object with layers of society’s expectation, the film’s take on those expectations, the actual delivery of the joke in context, and the reception of the joke in the film (to breakdown how my brain works, simply). These layers are like an equation (not to bring math into this); you can subtract the delivery from the societal expectations, add the film’s take, and divide by the reception:

When Richard Jenkins tells John C. Reilly and Will Ferrell that he used to be a dinosaur, society expects a fatherly pep talk, Jenkins delivers it masterfully as a straight man, but it is wildly unexpected from his character in context, and the joke lingers on an incredulous Reilly and Ferrell

Fatherly pep talk is delivered flawlessly with unexpected content and lingers for effect = comedy gold AND excellent, effective advice that becomes the moral of the movie AND potentially an angle of entry for analyzing the film’s commentary on class dimensions of goofy wealthy white men and their financial freedom to be dinosaurs despite nature’s laws

We can analyze the intent and effectiveness of comedy based on those expectations of both society and the genre conventions a film is embracing. But all of that goes out the window when comedic geniuses decide not to make a comedy at all at which point analyzing the comedy becomes a lot harder, and I really respect the ZAZ writing team for fully embracing that kind of framework for their spoofs.

The Naked Gun is, in effect, a drama. The beats of the film follow a dramatic structure: a cop is shot and put into a coma by a heroin ring that is inadvertently involved in a plot to assassinate the Queen of England on a state visit to the US. That’s not a light-hearted story with low-stakes. Ferris Bueller didn’t skip school for the day and accidentally kill OJ Simpson. The film follows that story structure of a high-stakes drama, has all the twists and turns one would expect with seduction and intrigue and film noir lighting all over the place, and then it garnishes those dramatic beats with some of the finest comedy since Chaplin’s little dinner roll dance.

Using a drama structure decimates the film’s expectation part of the equation, and Nielsen’s deadpan delivery and refusal to acknowledge the absurdity of his context - apart from when he stabs the $20,000 fish - sends the joke reception bit off the charts. The surrealism of the comedy almost defies a critic’s ability to parse individual jokes for social commentary, but the brilliant thing about the ZAZ brand of comedy, like Mel Brooks before, during, and after them, is that even their most absurd jokes are multiplied by the dimension of the genre they’re spoofing. So, killing a $20,000 fish with a priceless, one-of-a-kind art piece at the exact moment the detective is meeting the man the audience knows to be the bad guy adds a dimension of Frank Drebin’s lethality and the fragile vulnerability of Ricardo Montalbán’s strongman.

This kind of comedy in this film serves a real plot enhancing or furthering purpose. We get these absurd moments that magnify the dramatic beats without breaking from them. At the start of the film, OJ kicks in a door, but his foot gets stuck. Classic slapstick. Because his foot is stuck, however, the bad guys have time to reach for their guns and aim them at the door while OJ bucks like a bronco loose on the Santa Ana Freeway trying to free himself. Not all comedy serves a plot purpose and it doesn’t have to, but I am partial to really clever uses of comedy, especially smart slapstick and propwork, which really stems from my hatred of Bob Hope’s never ending prop bits in his 1951 Christmas comedy The Lemon Drop Kid.

The Naked Gun, on the other hand, is exceptionally thoughtful about its timing, prioritizing dramatic timing in place of comedic, which, of course, elevates the humor even more. It knows when to drop a joke, when to air emotion, and when to end the film before overstaying its welcome. So, taking a cue from ZAZ,