Righteous Impatience for Dinner and Progress

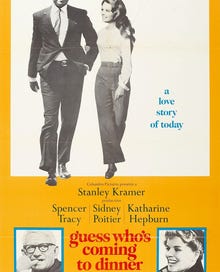

An Apparatus Approach to Guess Who's Coming to Dinner (1967)

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) – Apparatus

Happy Thanksgiving to all celebrating! Contrary to popular belief, Thanksgiving is my favourite holiday by far. I love the lack of expectations for the holiday, and I especially love cooking for my loved ones. I have been known in the past to have “Practice Thanksgiving” to experiment with new ideas and flavour combinations or try to make a dish that came to me in a dream (tarragon and orange cornbread drizzled with a Chablis syrup (yes, it was sublime)). So, as we gather round with loved ones and try to avoid certain topics of conversation while consuming the most crucial element of the meal that holds the key to all flavours in its sweet, jellified, cranberry ripples, let’s give thanks for some of the finest actors in Hollywood history giving us the gift that is Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967).

The Review Roulette wheel landed on Apparatus as our approach for this week which, for Thanksgiving dinner, works almost too well. As a reminder, an Apparatus approach concerns the ideological structures (apparatus) of society, asking what the film is reflecting, critiquing, or musing on in our society. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner doesn’t hide it’s ideological leaning at all, but I want to focus on one aspect of how the film constructs that ideology.

Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner is about one afternoon into an evening during which an all-star cast holds a bold mirror to society. We have several couples at the centre: Joanna “Joey” Drayton and Dr. John Prentice (Katharine Houghton and Sidney Poitier); Joey’s parents Christina and Matt (Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy); and John’s parents Mary and John Sr. (Beah Richards and Roy E. Glenn Sr.). Joey and John have fallen in love in a whirlwind romance over 10 days in Hawaii and have returned to their regular lives to inform their parents of their intentions of marriage. The catch is that Joey is a white woman who has fallen in love with a black man in 1967.

Now, this film could have taken an easy out and had Matt and Christina be unapologetic racists, white supremacists who flat out reject their daughter’s relationship or even disown her for bringing John into their home. But it doesn’t; it spends around 110 minutes pressuring liberals to confront the values they have been espousing for years. There is so much in this film that deserves to be discussed and considered and admired, but let’s narrow into specifically how age enters this conversation.

We’ll start with the Draytons. Matt is a newspaper executive whose paper has allegedly always taken a progressive stance on social issues, never shied away from standing firm with a moral position against hate. Christina owns an art gallery, an indication of her openness to creativity and the ways inventive passion can positively influence society. Matt and Christina raised their daughter in San Francisco in a very large white mansion high on a hill looking out over the city, Golden Gate Bridge, and bay. Their wealth and whiteness are fully on display, but we know that they also raised Joey to know that neither of those things make them better than anyone else. Joey was raised to reject hate, embrace inclusivity, and believe truly that all people were created equal. When Joey brings a black man home, both Matt and Christina are shocked, admitting that they never considered this might happen.

That shock is understandable. They were both raised in a far less progressive, segregated world and live currently in one in which interracial relationships were still illegal in at least 16 states. They had done their best to instil in their daughter ideals and values they would like to see in the world, and we know that Matt does a societal good with his paper presumably advancing arguments in favour of greater equality and rights for all. But now they are being challenged to decide whether those ideals about society are something they are prepared to live every day rather than just espouse.

Tracy and Hepburn are two unbelievable actors, and this might be my favourite performance of theirs I’ve seen (individually and together). (Also, if you don’t know about their romance, I think it’s one of the more beautifully complex human loves I know of and worth reading about). Their performances here (not to mention Poitier’s) are so smooth and natural that you really can see the metaphorical glass shatter. Matt and Christina’s lives have been outwardly progressive but still separate from every having to engage really with the values they are progressing, and when that distance from their mansion on the hill shrinks to the size of their living room, you can feel the confrontation on just their faces struggling to be the people they have claimed to be thus far.

That’s where the generational divide is so powerful. Matt and Christina, I think, are ultimately struggling far more with how society will view Joey and John and are primarily concerned with their safety from racists more than any concerns about racism in themselves. They have lived experience of segregation and are struggling to imagine a world in which an interracial marriage is a good, safe idea. Whereas Joey has been raised to be a confident, unapologetic progressive who does seem a bit naïve to the realities of white supremacy in America. Her progressive worldview and progressive parents have sheltered her somewhat from the harsher realities for the man she loves.

There too an age difference is fascinating because Joey, a 23-year-old white woman with limited life experiences, is 14 years younger than John, 37, who has experienced tragedy, hardship, and the societal pressures bearing down on a black man to be nothing short of perfect to excel as a doctor. John lost his first wife and young child in a train accident nearly a decade prior and has served communities on several continents to make access to medical professionals and education more equitable across the globe. He has experienced those harsh realties that Joey and her family have only taken displaced moral stands on.

Finally, we get the perspectives of John’s parents who have lived and worked throughout the 20th century in a divided and white supremacist America. John Sr. worked as a mail man for the USPS for decades to secure a pension and provide an education for John while it’s unclear Mary worked at all. Their life experiences have guided their reactions to the news of their son’s interracial love about which they learn in her family’s white mansion.

The generational divides are fascinating and play integral roles in the discussions that make up the film as characters cycle between each other for crucial conversations. It ultimately becomes clear that the fathers’ reservations are based in fear about the future while Joey’s unshakeable sincere optimism is based in her refusal (or inability) to see the world of 1967 in the context of their parents’ experiences earlier in the century. John is right in the middle with enough experience to know the hardships of the past and enough future left to want to fight for it.

It’s a precipitous moment in American history and this film holds that mirror up not to racists in our country but to the liberals who speak progressively and asking them to act on their words. It’s a beautiful film that challenges an older generation to meet the future and live the reality of the ideals they’ve fought for. Not only was it timely in 1967, but it also is unfortunately necessary for our moment today in the wake of a frustrating election that asked a lot of those similar liberals to act on their espoused beliefs. As we navigate discussions today about that election, I think this film offers a lot of grace and also righteous impatience for how to manoeuvre inter-generational conflicts and conversations about such topics. The rapidity of progress in our country can sometimes be seen as a curse, that we need to hold the hands of older generations who aren’t ready for the changes the younger generations want for their futures, but the beauty of Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner is that the older generation’s fears are acknowledged and also politely and respectfully refused as obstacles to progress.

I’ll end on a prescient note within the film: John and Joey met in Hawaii in 1967. In her infinite optimism and positivity, Joey believes their mixed-race children will be president some day with “colourful administrations”, and John jokes that he’d settle for Secretary of State implying the then-unlikely scenario in which that would be an American reality. In the span of their would-be children’s lifetimes, as their oldest would be 57 in 2024, they would have seen two black Secretaries of State (Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice) who were raised in segregated America, one mixed-race black and Indian Vice President (Kamala Harris), and one mixed black and white Hawaiian-born President of the United States of America (Barack Obama). Sidney Poitier’s influence on the ideological structures of society needs no embellishment or exaggeration so I won’t imply omniscience too, but the coincidence of John and Joey’s relationship (1967) and the reality of then-6-year-old Barack Obama one day becoming the first black POTUS is too iconic not to acknowledge.