The Devil's Own Switch Hitter

A Queer Approach to Damn Yankees (1958)

Damn Yankees (1958) – Queer

Happy fourth week of Review Roulette: Spooky Edition!

Halloween is coming but so is the World Series, so this week I figured we both it. A baseball story with a touch of the devil, what could go wrong?

Spoiler alert: Too much.

Now, I hope my loyal readers know how much I dislike panning a film. It’s not my style, even when I really am not vibing with a film. It is absolutely okay not to enjoy a film, that’s how art works, but I do think that there is almost always something to appreciate in a work of art. Negative feelings about cultural media we consume can often be highly productive ways of engaging with that material if we really sit with those feelings in constructive introspection. So, as I sit with George Abbott and Stanley Donen’s Damn Yankees (1958), I want to lean into the aspect of the film I enjoyed the most.

Little inside baseball: I spin the Review Roulette wheel before I watch the film each week so that I can watch the film with the lens it landed on. This guides my viewing and review for each film, and this week the wheel landed on Queer as our approach. I, being me, probably would have picked up on the queer vibes in the film a bit, but I think specifically viewing it with a queer lens helped significantly to see the playful campiness in the film.

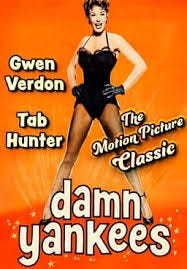

Damn Yankees is a Faustian musical, except instead of unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures, our deal-making hero wants one thing: for his baseball team to win a pennant (not even the World Series) against the proverbial damn Yankees. Diehard Washington Senators fan Joe Boyd (Robert Shafer) makes a deal with the devil, Mr. Applegate (Ray Walston), to become a 22-year-old baseball superstar by the name of Joe Hardy (Tab Hunter) to win the Senators the pennant himself. Boyd is smart enough to ask for an escape clause on their deal (but not for any other details about anything even remotely important) before transforming into Hardy, leaving his already neglected wife Meg (Shannon Bolin) with a note saying he’s just leaving indefinitely. As Hardy gets the Senators closer to victory, the devil throws wrenches in his way including his side-kick seductress Lola (Gwen Verdon) and her “sexy” moves.

There is a lot to unpack in this film, even with that basic plot. As a reminder, I have repeatedly used queer theory to analyse aspects of films that are non-normative: the Island of Misfit Toys in Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (1964), the questionable relationship in When Harry Met Sally (1989), and (probably my favourite review I’ve written) the exquisite friendship within a romantic partnership in Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994). This week, I want to lean into this film’s queering of cinema with its camp qualities.

One way to think of “camp” is as film in drag. It’s an exaggerated aesthetic, theatricality and excess and humour and artifice on display that subverts some level of straightness (read as “played straight, not tongue-in-cheek”) of a more traditional style. Hands down, the best character in Damn Yankees and easily the campiest is the devil, aka Mr. Applegate (whom I’m assuming is named for some loose connection with the apple in the Garden of Eden).

Ray Walston does an excellent job in this film straddling the line between straight and camp. He gives just enough camp with sly magic tricks, cheeky one-liners, and extravagantly stylish outfits to balance out his smarmy flirtations with women and more serious lines. As the film goes on, however, the devil’s campiness escalates and he becomes catty (legitimately even pretending to hiss and scratch others), petty, and just a little savage when he calls his right-hand girl Lola “my futile wench”.

This movie is an almost direct replica of the stage show put on film, so some campiness is expected, but I really do think they leaned in a bit, more and more as the film goes on. For instance, in one scene in the lavishly decorated bedroom we are meant to believe is hell, we see Mr. Applegate in a satin red nightie embellished with gold pitchforks – camp – juxtaposed with the purple satin wall décor and bedding – Camp – shortly after a random, unacknowledged witch (like black cloak, pointy hat, raggedy hair witch) opens the door for Joe in the background and disappears without a word – CAMP. At first I wasn’t vibing with this film, and I still don’t think I will ever revisit it after posting this review, but I respect the subtle campiness drastically increasing throughout the film in a completely unacknowledged way, to the point that there’s a final musical number that lasts far too long, ends with about 10 minutes left in the film to resolve everything, and has absolutely nothing to do with baseball or much of the rest of the film and kind of undermines the whole moral point that was made up until that point. Camp.

Without the camp, I don’t enjoy this film at all. With the camp, I think it opens up a wonderful queerness that throws everything else in the film into question, such as “why are the baseball players constantly breaking into song?”, “is it normal for individual players to have variety shows thrown in their honour with acts from multiple fan clubs?”, and “why is it a normal thing in our society for men to act so terrible to their wives because sports?”. Camp, just like drag, invites us to question norms when those norms are exaggerated or altered for enhanced theatricality. It subverts traditional expectations of normal cinematic tropes, presentations, and icons – such as those of the devil – in order to more closely and more critically examine features of those subjects.

Evidently the producers of multiple stage versions of the show agreed that the campiness was the best part of the show because of their castings of both the devil and Lola. Lola, who interestingly is the only character on the film’s poster and for whom the name is titled in the UK version (What Lola Wants), is the second campiest character with multiple quite unbelievable dance numbers. In her attempt to seduce Joe, Lola puts on a kind of Spanish accent(?) and does a kind of strip tease in the least sexy seduction I have ever seen – (the 4:00 minute mark is what actually qualifies this week as a Spooky Edition). Some casting pairs have been Bebe Neuwirth and Victor Garber later succeeded by Jerry Lewis; Jane Krakowski and Sean Hayes; and Maggie Gyllenhaal to Whoopie Goldberg’s gender-bent devil. And, of course, in the 1970s, Vincent Price starred as Mr. Applegate on the West End.

Viva la camp.

Because I’m Never Done When I Say I Am

Genre

I think the reason I was less than enthused about this film is that it feels very much like a stage show. The dance numbers are slightly too long, the pacing is off, the songs are a bit off in places – like at the fan club variety show, Lola does a number with the show and film’s choreographer (and the actress’s future husband) Bob Fosse that has literally nothing, absolutely nothing, not even a single tangential thing to do with the rest of the film. I also am not very sold on the romance aspect of the film, except for the one moment in which we realise that Joe actually does listen to his wife even when he’s watching baseball. But, at the same time, he acts as though she does not exist at all, so maybe it’s worse that he’s listening and actively ignoring her rather than simply engrossed in his sport-watching. Either way, it gently, perhaps even queerly, defies its genre and medium conventions.