The Economic and Moral Appreciation of Time via Aphorisms, Watches, and Orgasms

A Marxist Approach to She's the One (1996)

[Contains Spoilers]

She’s the One (1996) – Marxist

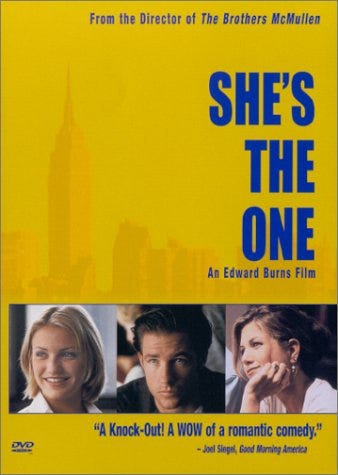

I have seldom seen a more morally and romantically chaotic film than Ed Burns’s She’s the One (1996). I am going to just say this one has spoilers because the whole film is an absolutely wild ride, and I won’t reveal everything but fair warning we cannot discuss this chaos without some spoilers. The Review Roulette wheel landed on Marxist as our approach this week and I will admit, I was and am a bit thrown, but let’s see what we can do.

If you haven’t had the genuine pleasure, She’s the One is a film about two brothers, Mickey (Ed Burns) and Francis (Mike McGlone), and their dad Mr. Fitzpatrick (John Mahoney) as they manoeuvre complicated romantic relationships and personal desires. All three have drastically different relationships: the father is long-married to their mother whom we never meet, Mickey abruptly marries a woman, Hope (Maxine Bahns), within 24 hours of meeting her, and Francis is married to Renee (Jennifer Aniston) but is in love with his mistress Heather (Cameron Diaz) who is also Mickey’s ex-fiancée. Chaos. Chaos and a phenomenal cast. Leslie Mann is also here but not in the main chaos. Tom Petty wrote the soundtrack too. And Robert Redford produced it. Chaos.

Okay. So, there is an obvious Marxist approach here which would be to compare the moral presentations of the two brothers. Mickey is a stand-up working-class man with ethics he sticks to steadfastly, even if he is a bit bristly in a stereotypical Brooklyn guy’s guy kind of way. Meanwhile, his brother Francis is a typical Wall Street take it all, have it all, never look down kind of guy who is, obviously, an asshole. These are surface level analyses though, so I want to look at three different angles that speak to the class-dimensions within the film: the brothers’ father, Mickey’s watch, and Francis’s driver Tom (Malachy McCourt).

Mr. Fitzpatrick is a really fascinating character who graces his sons with life lessons and wisdom on a fishing boat where girls aren’t allowed. The unfortunate part is that the life lessons and wisdom are a bit shit. The dad is so focussed on protecting his peace and encouraging his sons to do the same, find what makes them happy and do that thing, and it sounds like great advice through witty aphorisms. It’s delivered lovingly with light-hearted 90s jabs at one another that now are a bit homophobic, but you can see the dad loves his sons and wants to impart some sort of fatherly advice in this manly way as a tradition on a boat. I didn’t really question his character or his advice, he was a dad responding to his sons as he thought was best. That is until we see the reality of his own relationship and the dime drops that his proclaimed individualism and protected peace did not ever include that of his wife.

This is a real twist in the movie: the father figure holds himself accountable for his role in “messing up” his kids’ lives with “rotten advice”, however well-intentioned that advice was. The film concludes with quite a beautiful unspoken reflection from the father on the value of partnership and time. He apologises to his sons for giving them the bad advice that they acted on throughout the film in their own ways, actions that landed them in the complicated chaotic relationships we witness. It’s rare to see a film lean into the value of age and a reminder that you can always – at any age – reflect, grow, and correct yourself.

The second Marxist angle is via the watch. Mickey runs into Heather who originally gave him his watch while they were together years prior to the film. Heather demands the watch back and then regifts it to Francis, knowing that Mickey will see it and causing just that bit more chaos with her at the centre of the two brothers’ attentions. Mickey does not initially want to give up the watch but quickly decides it’s value as a gift and nice watch is far depreciated by its connection to Heather. When Francis receives it, the watch becomes a significant plot point, valued intrinsically by Francis as a gift from the woman with whom he is in love until its connection with her again depreciates its value when it causes conflict with his brother. Ultimately, the value of the watch is again restored when Mickey suggests they give it to a bartender as a tip, a person with no connection to Heather who could not possibly see it as anything but a sweet and expensive token of appreciation from two patrons. The watch has both a moral and an economic value that wavers back and forth throughout the film as the brothers struggle to correct their romantic and filial relationships. Ultimately, the two come to understand that the appreciation in moral value of quality time together is higher than the economic value of the high-quality time-telling device itself.

Finally, Francis’s driver Tom still gives his wife orgasms at 68 years old, according to Tom’s wife (allegedly). Tom’s role is largely comedic relief as an outside character whom we only see a handful of time and only through the rear-view mirror as he drives Francis around Manhattan. He functions as a working-class sounding board for Francis’s delusional thoughts about his value as an “man”, and each time Tom respectfully and politely puts him in his place. In the first such interaction, Francis asks Tom if a man “at his age” is still able to have sex. Tom responds jovially that he, of course, can – he is only 68, but Francis’s mentality as a 25-year-old alpha male type (who would definitely be espousing the benefits of cryptocurrency if this film were made now) is garbage. Having humiliated himself in front of Heather who had three orgasms with her older partner, Francis then asks if Tom can still “perform” to which Tom answers his wife says he’s better now than he was in his 20s.

This scene plays for laughs with Francis’s discomfort – or really, disgust – when asking and Tom’s excitement to answer, but it does have, again, quite a surprising message that isn’t often celebrated in a lot of cinema: aging is beautiful. We all get better with age. We reflect, we grow, we become more attune with our loved ones and if we don’t we have the opportunity to correct that course if we choose to. It’s quite a radical sentiment that ultimately celebrates time as a fast-moving thing you can slow down every once in a while to reexamine and readjust before it speeds by again. The film itself feels quite fast-paced with all its chaos, but the cadence – upon reflection after I have stepped out of its speed as modelled in the film – is actually very well paced as a reflection of (an admittedly absurd) life and a celebration of slower moments – a flip of the film’s recurrent “down-cycle”.

This film really is chaos, but it’s quite beautiful chaos. I frequently come to appreciate a film even more after having written a review (like I said last week about The Conversation) and I really think I agree with that again here. Plus, a soundtrack with Tom Petty never hurts the soul (even if it isn’t his finest (apart from “Walls” (a more than perfect song))).

Because I’m Never Done When I Say I Am

Gender

She’s the One isn’t about a woman in the end. It’s barely even clear who the titular “she” is referring to, and I think that’s really wonderful for a film remembered as a romantic comedy. The strength of this film is in its dedication to its three main characters, Mr. Fitzpatrick, Mickey, and Francis. While Francis’s character is quite toxically masculine (by today’s terminology), the film itself is about male bonding, men reflecting on their actions towards women, men challenging each other to be more compassionate, men sharing their emotional wants, needs, and desires with the other men in their lives. It’s pretty radical and offers a very rare model for that male-centric self-reflection that I do wish we had more of in Hollywood. Of course, She’s the One is an independent film, though.