Jokes and Mirrors: Using Cartoons as Primary Sources for Historical Research

A Media Literacy Lesson Plan

Dear readers,

I broke my thumb, and I’m in a shit-ass mood about it. I’m also in a shit-ass mood about the state of the world, especially the US, and one way in which I am uniquely qualified to help with that is by promoting media literacy, one of our biggest failings as a society right now. So, I try to make sure my scholarship is Open Access because watching the world crumble while most of our scholarly resources are behind paywalls is actually giving me a chronic eye twitch. My earliest publication is not OA though, so I’m putting it here in the absence of a review this week because typing one handed is contributing to the aforementioned shit-ass mood.

This article is a how-to guide for using cartoons as historical primary sources. It is laid out as a self-guided lesson plan, but please feel free to use it in whatever ways are helpful to you or your students or whomever you want to share it with. The case study used is a cartoon of Jefferson Davis running from Union officers in his wife’s skirts. Enjoy.

Jokes and Mirrors: Using Cartoons as Primary Sources for Historical Research

A Case Study from the American Civil War

Abstract

Cartoons are important and rich primary sources for historians. From hand-drawn caricatures to comic books and digital memes, cartoons for centuries have been a medium in which a mass audience can relate with their surrounding social and political worlds. Cartoons can be evocative of emotional responses, vectors of escapism, webs of metaphorical and artistic renderings of key historical figures and events, and satirical commentaries on life in the past with biting humour and careful rhetorical composition. Due to this multidimensionality, cartoons can be read as social or cultural mirrors, capturing the sentiments of a time in even a single panel of expressive drawings. By combining approaches such as reading cartoons as rhetorical devices, thinking about the physical context of the image at original publication, considering its viewers’ responses if available, and fitting the cartoon into its contemporary social world, historians can use cartoons as rich sources for political, cultural, and social commentaries. This case study will explore how a cartoon from the Civil War depicting former Confederate President Jefferson Davis fleeing from Union officers can be used as a social mirror for Chicago, as well as a reflection of wider attitudes towards gender, in 1865.

Learning Outcomes

After reading this case study, you will be able to:

Identify the various types of cartoons and choose an appropriate methodology for your study.

Interrogate an editorial cartoon for social commentary.

Contextualise a cartoon by identifying the social and political environments in which it was created and published.

Discern the tone and possible intended messages of a cartoon.

Utilise a cartoon as a primary source for historical research to deepen your understanding of the social and cultural ideas within the time and place of its creation.

Initial Steps and Questions

Before reading this piece and evaluating the primary source in full, you may want to reflect on these questions and initial steps:

The initial step in interrogating a cartoon for historical research is to determine the methodology – or combination of methodologies – you want to consider using in your analysis. Some common approaches for historical analysis of a cartoon include reading the cartoon with Rhetorical Analysis, employing Meta-Cartoon Analysis, examining the cartoon through Reception Studies, and viewing it as a Cultural or Social Mirror. Rhetorical analysis includes examining the levels of satire used within the cartoon, reading symbolism and metaphorical portrayals, discerning the tone of the content, and questioning the arrangement of visual depictions to elicit a desired effect similarly to how one would analyse a speech or written document. Meta-cartoon analysis involves thinking about the cartoon in wider contexts of its creation, production, and publication, thinking about the cartoon as an object. A meta-analysis is best for cartoons of which the artists are known and accessible in histories or for those which are part of a larger series, stylistic trend for an era, or entrenched in a larger document. A meta-analysis, for instance, would ask what the purpose of this cartoon is as a seemingly index-card sized print; did people collect these cartoons or was this cut from a larger publication with the agent’s information printed on the back later? Reception approaches to cartoons seek to understand the distribution of a cartoon, who the viewers were, and how they would have reacted to the messages within it. Reception studies foreground the audience and any records of written responses to cartoons. This type of study is ideal for cartoons with editorial responses such as comic books with letters to the artists and writers.

Viewing a cartoon as a cultural or social mirror places the cartoon in direct dialogue with popular attitudes around the time of its publication. This methodology extends the rhetorical analysis and can include meta-cartoon analysis and reception studies, when available, by explaining the possible underlying, synchronistic public perceptions around the subject matter of the cartoon.1 Determining whether a cartoon is a cultural or social mirror also can be approached with theoretical perspectives such as gender or Marxist theories concerning the cartoon’s content, production, and/or distribution. Establishing a reliable cultural or social mirror is best done with a mix of the first three methods – rhetorical, meta-cartoon analysis, and reception – and will be used for the case study below.

Depending on the type of cartoon you are analysing, there may be additional or varying steps to consider. For instance, you might consider the following: if the source is a cartoon of opinion or a joke cartoon, if it is commissioned propaganda, if there is or is not text within or in dialogue with the cartoon, if information is accessible about whether the cartoon is from a series or freelance cartoonist, or if the cartoon in question is an internet “meme” or a traditional print media cartoon. For this case study, we will focus on the sketch of Jefferson Davis from the American Civil War: a single-panelled political – or more widely known as an ‘editorial’ – cartoon sketch printed in traditional fashion with little known about its publication.2 Additionally, when analysing cartoons, we use the term ‘content’ for pictorial representations, the image you see when looking at the cartoon, and ‘subject matter’ for the wider societal context. In this study, the content of the cartoon in question is President of the Confederate States Jefferson Davis wearing a dress and running from Union officers, while the subject matter is Jefferson Davis and the American Civil War.

To analyse this type of traditionally printed editorial cartoon, this case study combines viewing the cartoon as a social mirror with rhetorical analysis, meta-cartoon analyses, and speculation about its reception.

Initial Questions

What is depicted in the cartoon, and, if evident, what is the subject matter of the cartoon? This question asks who or what is portrayed in the cartoon, the content, and normally gives insight into historical context if the subject matter is overt. Sometimes, the subject may be vaguer, hidden behind metaphors and artistic licensing that lend the cartoon to multiple interpretations or time periods with similar events, in which case, archival details will assist in locating the cartoon temporally and locally. In this event, the archival date and publication information, if available, can help to narrow down a time frame or exact publication date and historical event to help determine the subject matter.

What type of cartoon is it? Is it an editorial cartoon, a joke cartoon, a piece of commissioned propaganda, a comic strip, a single image from a series, a digital cartoon? In answering this question, you can discern the scope of the cartoon and decide whether additional meta-analysis is appropriate for your study. Additionally, identifying the source type can also inform the tone of the cartoon and influence your reading of the commentary being made. For instance, cartoons with political messages published in children’s magazines or comic books will have a different tone and message than a political cartoon in an adult’s newspaper.

Is the cartoon a caricature or stereotype of a person, place, object, or historically significant event? A caricature is an exaggerated depiction that chooses one or several identifiable characteristics of the subject to depict either farcically or satirically. A stereotype can be a generalisation about the subject that may or may not be true of the individual subject but rather is representative of a cultural idea about the subject. Answering this question can inform the tone and level of satire intended, as well as the artist’s interpretation of a historical event.

Is there any text on the image or accompanying it in a printed column or essay? Text on the image can help contextualise the cartoon historically and indicate the social commentary of the piece, such as a political argument being made. Accompanying text can also be a clue as to whether the cartoon is a visual metaphor or allegory for the subject matter.

Who created this cartoon and where was it published? Has this cartoon been mass produced for the public, or was it intended for personal or private consumption? Information about the cartoon’s publication, if known, can be found in the archival description for the source. Identifying the audience of the cartoon can be an important indicator for contextualising the subject matter and understanding the message. Additionally, with the increase in digital technologies and platforms in the twenty-first century, cartoons of more modern study could include memes, web-comics, and non-traditional media platforms designed for rapid dissemination and sharing. It is important to understand what context the cartoon was created for, as well as viewed in, around the time of creation.

Contextual Information

Throughout the latter twentieth century, social history evolved from largely Marxist roots to include cultural and linguistic trends associated with poststructuralist thought. These approaches have created a vibrant field of special topics and invigorated the use of new source bases to gain a better understanding of the history of everyday people in the past.3 Cartoons are one such source that deserves further special attention for how they can be used in historical research.

In existing scholarship, there is no distinct field dedicated to the study of cartoons. Many fields sometimes use cartoons as primary sources; however, historians in the early twenty-first century have made attempts to synthesise approaches into paradigms that could shape a cohesive field devoted to cartoon history specifically in the future. Khin-Wee Chen, Robert Phiddian, and Ronald Stewart in their 2017 chapter ‘Towards a Discipline of Political Cartoon Studies’ chart the different ways in which cartoons are approached in various fields and call for a streamlined historical perspective.4 Citing authors such as Robert Cuff as early as 1945 through Thomas Kemnitz in 1973 to Sheena Howard and Ronald Jackson in 2013, Chen et al. examine how the use and importance of cartoon research have grown over time particularly for historians who utilise cartoons as cultural and social mirrors of the past.5

When using a cartoon as a cultural mirror, it is essential to understand the social and historical context of the cartoon’s subject matter. This section of the case study will explore the context of the cartoon depicting Jefferson Davis in a dress fleeing from Union officers so as better to understand the message of the cartoon and the ways in which we may use the cartoon for deeper insight into cultural attitudes at the time of its creation.

The American Civil War ended on April 9, 1865, when Confederate Commander-in-Chief Robert E. Lee formally surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at the Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Less than a week later, on April 15, 1865, United States President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated in Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C., making Vice President Andrew Johnson from Tennessee the new president. In the aftermath of the bloody war and the murder of the president, the new United States President Johnson charged former President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, with complicity in the assassination and offered a $100,000 reward for his capture.6 The pursuit of Jefferson Davis lasted until the dawn of May 10, 1865, when the Fourth Michigan Cavalry caught up with Davis and his entourage in their encampment near Irwinville, Georgia.7

When Jefferson Davis’s scouts woke him to warn that the Union officers were closing in, Davis was disoriented and dressed in a rush to make a quick escape. In his haste, Davis mistakenly dressed in his wife Varina Davis’s garments and was captured shortly after. This mistake quickly circulated around the country and resulted in caricatures, such as the cartoon in question, and ridiculing articles depicting the former president in petticoats, bonnets, and even full dresses while attempting to escape.8 Jefferson Davis made multiple attempts to regain control of the narrative after the nationwide spectacles of derision and shame directed towards the proud South. In 1869, Davis had a picture taken in the clothes he allegedly wore when captured to dispel the rumours about dresses and bonnets.9 In the second volume of his 1881 memoirs, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Jefferson Davis recounted the situation with a two-page passage about the events of the morning. Davis states his wife ‘implored [him] to leave her at once’ and confirms he pulled on a ‘“raglan,” a water-proof, light overcoat, without sleeves; [which] was subsequently found to be [his] wife’s’.10 These attempts at clarifying the situation came too late and many eye-witness accounts confirming the simple mistake were disregarded, as Davis’s image and this event had already been ridiculed and caricatured in exaggerated cartoons across the country.

Understanding this historical context around the subject matter of the cartoon, we may now turn to the cartoon itself. It is essential to lay the foundation of historical context for the image, so that we may appropriately apply any theoretical approaches in our analysis, engage properly with the historiographical debates and secondary literature concerning the subject, and more accurately determine the effectiveness of using the cartoon in historical research.

Source Analysis Questions

Consider again the initial questions: what is the content, subject matter, type of cartoon, and tone? Is there a caricature or stereotype used? Who created it? Information about these descriptive and meta-analytical questions can normally be found in the archival description provided with the cartoon and upon observation of the image. If the artist is known, biographical details should be researched.

If there is text within or accompanying the cartoon, what is the relevance? What is the combined intended message from the text and symbolism within the image? When cartoons have text, we can better comprehend the context and intended message of the cartoon. Sometimes the text is a metaphor, an allusion to another work, a straightforward commentary on the subject, or a satirical, sarcastic joke. Additionally, one should consider whether the cartoon is on its own or published in a newspaper with accompanying articles or opinion pieces about the subject matter. Do these additional texts influence your reading of the cartoon in any way? To understand the text in dialogue with the picture and its symbolism, the tone should be considered as well as any information about the intended audience and background of the creator or publication in which it may have featured.

Where was this cartoon published and by whom in this wider social context? What do we know of the physical copy if the cartoon is digitised, and how might this change your interpretations? Considering this question again with further research into the historical context will impact your analysis of the cartoon. If the cartoon is an editorial, one should question whether that level of politicism was government-sanctioned or a challenge to authority. In some areas and time periods, satirical cartoons about the government are or have been considered defamatory and illegal. How does this impact the creation and publication of the cartoon? Is the cartoon positive or negative about the government under which it is being published, that is, is this cartoon propaganda? Additionally, here you may consider the physical dimensions and materiality of the cartoon if known or observable, determining the medium in which it was created. For example, is the cartoon the size of a postage stamp or a poster in a public setting? How might the physical nature of the cartoon impact your analysis?

Are there any similar images or cartoons in circulation around this time? Sometimes the images depicted in a cartoon have been reproduced elsewhere and, frequently with editorial cartoons, the subject matter is referenced in other contemporary cartoons or publications. If there are other cartoons concerning the same subject or depicting similar (or contrarian) content and imagery, this can be strong evidence in discerning the reliability of the cartoon as a social mirror.

How does this cartoon fit into the wider social context around its publication? Placing the cartoon contextually within the history around its subject matter is crucial. This can be done in multiple ways depending on the theoretical framework you want to use for your analysis. For example, if your subject matter has a class dimension, you might want to consider a Marxist approach. This approach would question what class dynamics were like around the time and place of the cartoon’s creation. Were there class-based revolutions around the time, large-scale creations of unions, new legislative measures in place to suppress or assist workers? Fitting the cartoon into the social, political, and cultural context, while thinking about the audience and creator of the cartoon, gives deeper insight into understanding the intended message.

How can this cartoon be used as a primary source? What can the cartoon tell us about the social context around its creation? Can the cartoon be used as a reliable social mirror to give insight into a contemporary social commentary? Research into the cartoon’s subject matter, social context, place of creation and publication, and the accuracy of the representations of events and people influence the analysis of the source. Determining whether the cartoon is a reliable social mirror can be done by comparing the image to other historical research about the context with other sources confirming or denying the existence or scope of the message within the cartoon. Cartoons can themselves be excellent sources for understanding the prevailing views of certain groups in society depending on what is known about the social attitudes of the period from external sources and/or with publication details such as where they were published and what the demographics of the publication’s readership were.

Critical Evaluation

Introduction

As explored in the historical context above, this cartoon of Jefferson Davis fits into a wider narrative of the end and social ramifications of the American Civil War. To critically evaluate this source and understand how this cartoon may be used as supporting evidence for a larger thesis in one’s historical research, we will look at the questions posed above and bring in the necessary secondary literature to support analytical conclusions.

Introducing Cartoons as Sources

Cartoons are a rich and underutilised source in historical research. The term ‘cartoons’ can encompass many types of visual media. For this case study’s purposes, ‘cartoons’ are defined as any artistic rendering that invokes a social or political context, normally in response to an event, person, object, or place. This definition includes but is not limited to hand-drawn caricatures, lithograph printed drawings, bound comic books, and digital memes. All types of cartoons are powerful artistic devices that have the ability to transcend social class dimensions and audience demographics in ways the written word cannot.11 For example, cartoons can be mostly understood by an illiterate audience, and they can evoke an emotional or personal response – such as escapism or the feeling of inclusion in a societal joke – in the viewer through evocative depictions that words alone may not convey.12 The visual artistry of cartoons is not necessarily nor normally created as ‘high art’ for ‘high culture’, but rather is frequently created for a mass audience’s accessibility with prominent cultural touchstones, and so the appeal for historians to use cartoons is in this transcendent nature. Cartoons also can be interpreted in myriad ways, as any art can, often with layers of meaning, metaphor, and messages embedded within.

Cartoons, by nature, are multidimensional and artistic representations of their subject matter. Due to this multidimensionality, there are many different approaches one may adopt, and the method you choose will likely mean your conclusions differ from other historians studying the same piece. Additionally, cartoon history is not yet a distinct field in its own right as of the early 2020s. At the moment, it is a subgroup in other fields such as political history, the history of comics, media studies, humour studies, et cetera, each with their own approaches for the type of analysis the historian wants to conduct.13

Examining the Cartoon Sketch of Jefferson Davis

Having previously established the subject matter above as that of Jefferson Davis’s ridiculed attempt to flee the Union officers in May 1865, consider the content in this context. The cartoon depicts Jefferson Davis jumping over a wooden fence in a dress and bonnet as he flees from two Union officers. One officer is holding a sword in one hand and a lit torch in the other above the second officer who is pointing a revolver at Davis with a speech bubble that reads, ‘Hold on old Jeff! the “last Ditch” is not on that side of the Fence’. Beneath Davis is a bag reading ‘J. Davis Mexico’. Davis responds saying, ‘I thought your Government was too Magnanimous to hunt down Women & Children’. A woman in an ornate dress comments on the scene, ‘Don’t Irritate the “President” he might hurt somebody’. The cartoon is captioned ‘THE CONFEDERACY IN PETTICOATS’.14

This cartoon is an editorial commentary seemingly on the capture of Jefferson Davis in the month after the Civil War ended. Knowing the context of the rumours about Davis’s capture, we can surmise that this cartoon is a caricature exaggerating the type of clothing Davis was found wearing that dawn. Tonally, this cartoon is visually mocking Jefferson Davis making it a form of satire. With this conclusion that the cartoon is visually satirical, we can examine the language used in the image and further understand the intended message.

The text, as written above, can be analysed from many angles. First, the officer who remarks ‘the last ditch is not on that side of the fence’ could be referring to Davis’s weeks-long evasion of Union forces with a bounty on his head, or possibly to an inclination that the Confederacy were not ready to ideologically concede, despite the formal military surrender the previous month. Secondly, Jefferson Davis’s comment on ‘your Government’ is further context of the prevailing Northern view that Southerners saw themselves not as a defected part of the same Union as Northerners, but rather as a separate entity entirely still with Davis as the rightful president. His claim that the United States government ‘was too magnanimous to hunt down women and children’ can be read as both ridiculing Davis’s lack of courage so as to disguise his sex to escape and praising the North’s perceived benevolence and morality in its treatment of citizens from the South. Third, the woman’s commentary puts ‘president’ in quotation marks denoting sarcasm or illegitimacy to the formal title, and the suggestion that he may hurt somebody could be a reference to the charges against Davis of complicity in Lincoln’s assassination. Finally, the captioned title, ‘the Confederacy in petticoats’, is an openly satirical reference to Davis’s dress. All of this dialogue grounds the image firmly in the context of the capture of Jefferson Davis as described above and exposes the satirical verbal commentary mocking him, matching the visual tone already examined.

The text on the bag identifying Jefferson Davis also has the word ‘Mexico’ on it. This could be an allusion to Davis’s service in the Mexican-American War or possibly to his intentions of fleeing to Mexico after the war. This latter intention, however, was stated in a letter to his wife in April 1865 and whether it would have been common knowledge enough for a cartoon to make this reference requires further scrutiny.15

Contextualising the Cartoon’s Publication

Now that we have analysed the cartoon visually and understand the components of the image itself and how they relate to the subject matter, we can broaden our scope out from the image to the cartoon as a contextualised source. In doing so, we must envision the cartoon as a physical object, questioning such aspects as to how big or small the cartoon is if known, what materials were used to create it, who created and published it, when and where it was published, and how all of these contextual matters help fit the cartoon into the social world around it.

Regarding the publisher of this specific cartoon, on the reverse of the image is printed ‘Published by R.R. Landon, Agent, 88 Lake Street, Chicago’. Searching for a publisher can be a difficult task, especially for older more obscure pieces. Frequently, library and database searches for the publisher can come up with little or no related responses, as was the case for this publisher. It is always beneficial to spend time searching for as much information about the publisher as can be found and with varying punctuation in your searches, as this can greatly aid your research, date your piece, and add to your analysis of the cartoon as a reliable social mirror. One way to go about finding a publisher is to search the archive in which your cartoon is found or archives containing similar cartoons for any mentions of the publisher in other source descriptions.

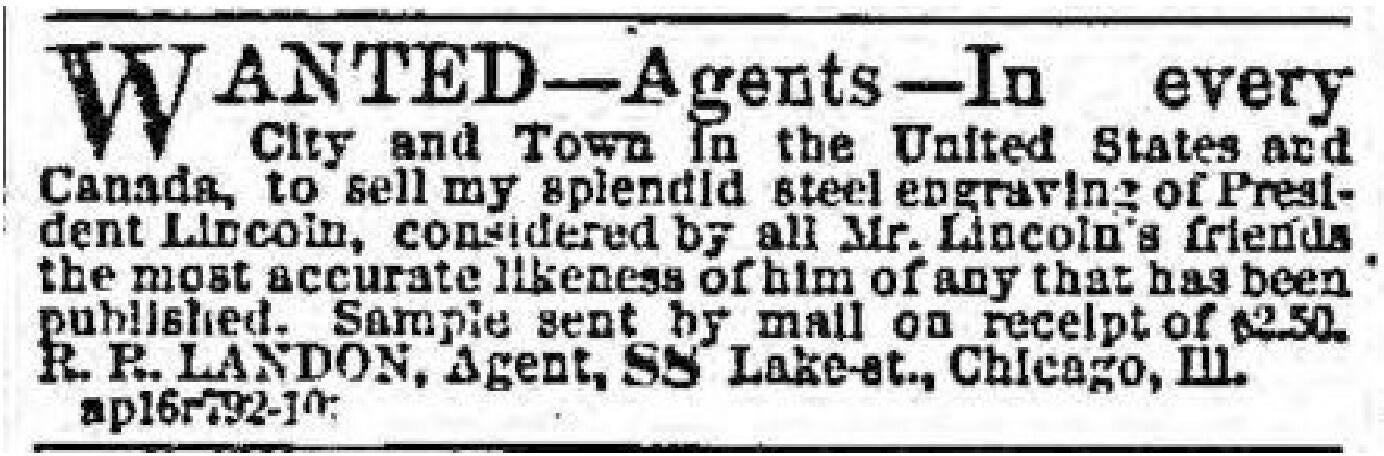

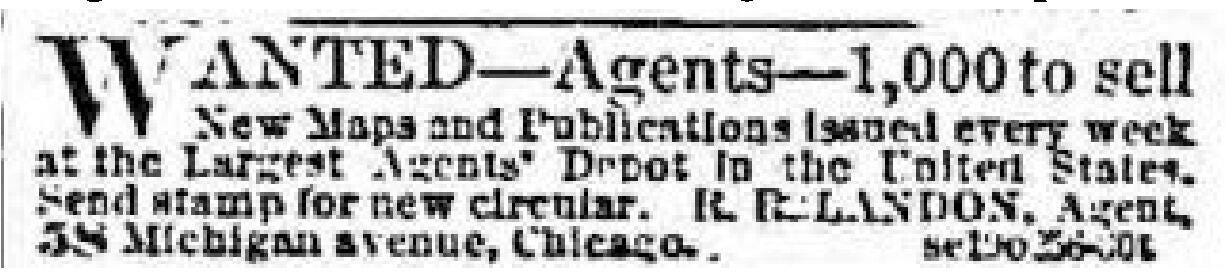

Searching in the Library of Congress catalogue for ‘"R. R. Landon"’ yielded 160 editions of the Chicago Tribune and The Press and Tribune also from Chicago between 1859 and 1872 in which R. R. Landon’s agency published advertisements. Examining them closer, we learn that R. R. Landon’s agency published and sold a number of print media sources including the Schönberg World Atlas in 1865 and a steel engraving of Abraham Lincoln immediately after his assassination in April 1865 (Figure 1). The wanted advertisement in Figure 1 is seeking agents in ‘every city and town in the United States and Canada’, while the ad in Figure 2 seeks to hire 1,000 agents and refers to Landon’s agency as ‘the Largest Agents’ Depot in the United States’ in September 1865.16

From these advertisements and descriptions of the types of publications issued, we can extrapolate that Landon’s agency likely had a wide distribution with at least a moderately successful reach in the Chicago area – a Northern city in President Lincoln’s adopted home state of Illinois that provided many troops for the Union Army – if not nationally as well. Landon also was current on political matters and did not hesitate to publish political content. All of this suggests that the cartoon in question can be seen as a likely reliable social mirror for a Northern audience if Landon’s agency was as successful as it seems through the advertisements in these periodicals.

Additionally, the advert in Figure 2 has a different address for R. R. Landon that persists in multiple ads following this one, suggesting the offices moved. This detail aids in dating the cartoon before September 22, 1865. In the archive details, the cartoon is dated between 1861 and 1865; however, with this research and social context, as well as the added knowledge that other publications were depicting this event throughout 1865, we can plausibly suggest a more accurate date for this specific cartoon as somewhere between May 10, 1865 (the date of Davis’s capture) and September 21, 1865 (the latest possible date R. R. Landon was at 88 Lake Street).

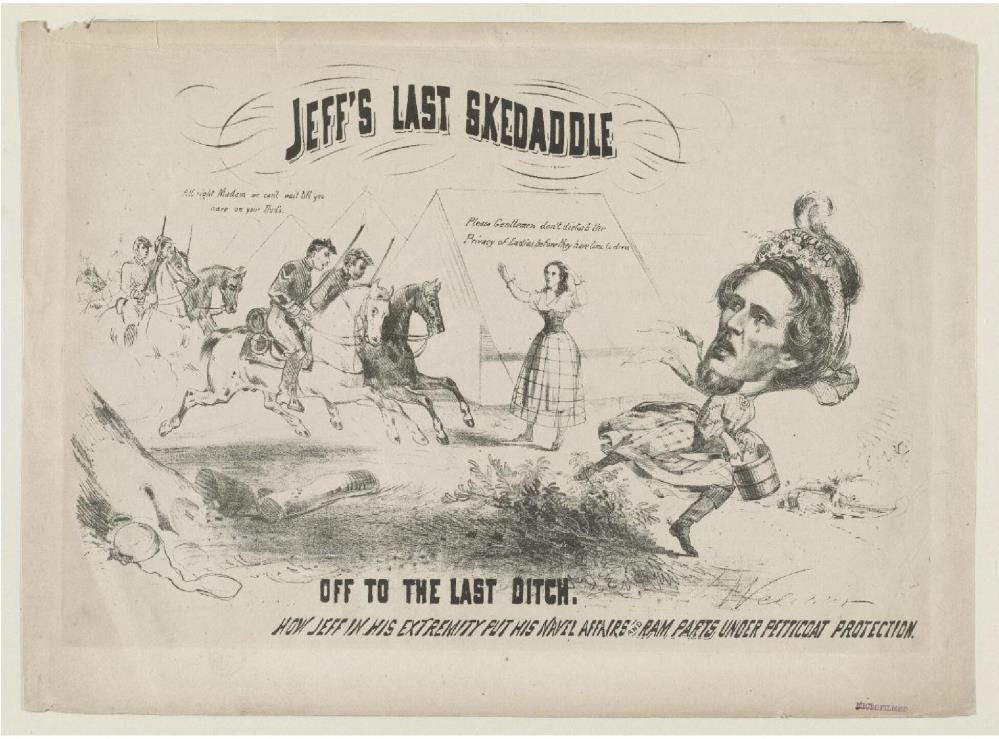

In addition to this cartoon, there were many similar contemporary depictions of Davis’s capture in circulation from larger and smaller agents. Publications such as The New York Herald, Harper’s Weekly, and The New York Times wrote scathing, sarcastic, and satirical articles and editorials on the disguise of Jefferson Davis that accompanied many of the visual depictions in exaggerated cartoons.17 Figure 3 shows one such satirical cartoon from F. Welcker, a popular cartoonist from the era.18

In deciding how to approach the wider social context, a number of theoretical avenues can be explored. For this example, I will show how to incorporate secondary literature and theory into our analysis of the cartoon as a cultural and social mirror through a gender history lens. Employing a gender history approach, we can read this cartoon as indicative of social attitudes towards femininity, masculinity, and gender performance. Historians writing on Jefferson Davis’s capture have highlighted the social context around his wearing of women’s clothing. Nina Silber notes that during the Civil War, there was increased hostility towards people evading capture by disguising their sex. This hostility towards ‘cross-dressing’, combined with the antagonism many Northerners had for the Confederacy and its president, fuelled an already existing narrative of ridiculing the previously esteemed masculinity of the stereotypical ‘Southern Gentleman’.19 Kathleen Collins and Ann Wilsher also comment on the tone of satirical and exaggerated publications writing about or depicting the events of Davis’s capture, concluding, ‘For ever after that May dawn, Davis has been condemned to scuttle through popular history, clutching his skirts and his shawl, shrivelled by the contempt of the North and the shame of the South’.20 Prominent social attitudes towards defaming the Confederacy’s former president were present throughout much of the North and were depicted by portraying Davis as transgressing contemporary gender norms.

Using the Cartoon as a Primary Source

With this critical evaluation of the source and its social context, we can now consider how this cartoon may be used as a primary source. Thinking about the creation, publication, distribution, and social world into which it was distributed, is this cartoon demonstrable of a prevalent attitude or sentiment that can tell us something about the cultural climate of 1865? In other words, we can now determine whether this openly satirical cartoon of Jefferson Davis fleeing from Union officers in a dress is a reliable source and a trustworthy social mirror as relative to a certain demographic. Further, we must decide what the limits of that demographic are and the degree to which we believe this reliability to be.

I propose this cartoon can be used as a reliable social mirror when considering the amount and variety of other publications utilising the same satirical tones as this cartoon, the historical evidence from Davis himself validating the subject matter, and the social contexts of antagonism towards Davis by Northerners in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. The cartoon – and many others – openly mocks and ridicules the former president, suggesting a widespread Northern sentiment of superiority after the war and even refers to Northern governance as ‘magnanimous’. This widespread Northern sentiment is supported by historians such as Silber and Collins and Wilsher as cited above.

As the cartoon relates to its social surroundings, Jefferson Davis’s depiction can give us insight into contemporary gender commentary. When viewing the piece in terms of gender attitudes at the time, the cartoon implies disguising one’s sex as feminine through clothing is cowardly and reflects prevalent contemporary attitudes of contempt for the practice of ‘cross-dressing’. In these ways, this cartoon can be used in numerous manners as a primary source and social mirror as support for Northern attitudes towards Southerners and the Confederacy, as an indicator of social attitudes towards femininity and masculinity, as a source for attitudes towards transgenderism and transvestism, and as a local piece of Chicagoan attitudes, especially when compared to sources from other cities and publishers.

Conclusion

Cartoons are multifaceted sources that can aid a historian greatly in capturing public sentiments in a particular era. Whether analysing a cartoon’s rhetorical features, text, and symbolism to understand the cartoon as an artistic expression of a cultural view or examining the cartoon as a social mirror with a theoretical framework better to understand prevailing attitudes on a specific subject, cartoons are rich resources. The multidimensional nature of cartoons and the myriad interpretations they can elicit when approached with different methodologies offer historians insight into how cartoonists perceived and reflected the world around them, how audiences may have understood them, and how political messaging and propaganda can be disseminated in everyday media to the general public.

Post-evaluation Questions

How might this cartoon have been received by citizens in the Southern US or Confederate soldiers who served under the government of Jefferson Davis?

What other social theories could you apply to view this cartoon in a different light? For instance, what further analysis could be made of this cartoon if utilised in a gender history of the 1860s? What could be read of the masculinity portrayed by the Union officers’ stances in relation to Davis’s positioning?

How might knowing more about the publication and dissemination data of this cartoon influence the analysis above?

What impact might this type of cartoon ridiculing the Confederate President have had if the war had not ended just prior?

Thinking about your wider argument and thesis, how might cartoons be a useful body of evidence? Does your analysis of the cartoon agree or disagree with the larger historiographical debates around your subject and how might it help to answer a historical question in the field? How might other historians’ analyses and interpretations be used to support your broader argument?

Further Research Considerations

If you were to research this area further, you might consider the following questions and discussion points:

Think more on the symbolism of objects in the cartoon. For instance, consider whether there is a rhetorical or metaphorical purpose for the torch in the officer’s hand or for the phrasing of ‘the last ditch’ that may influence one’s reading of the cartoon.

Compare the sketch of Jefferson Davis published by R. R. Landon with Figure 3, ‘Jeff’s Last Skedaddle’. How do these cartoons differ? Do any conclusions about the original cartoon as a social mirror change?

Consider other forms of war media and propaganda such as art, poetry, and songs that can influence the general public’s views and serve as a social mirror in conjunction with this cartoon. Search for more Civil War editorial cartoons and apply the methodologies outlined above to get a better understanding of how cartoons were used in wartime and for what reasons.

Explore how other historians have analysed this or similar cartoons to draw their own conclusions and form theses about the subject. What kinds of arguments can be made using your analytical conclusions about the cartoon, and how might they fit into the wider historiographical debates around the subject matter?

Read more about the types of cartoons and consider how cartoon propaganda, editorial cartoons, and joke cartoons can influence different audiences. For instance, an editorial cartoon published in the Southern United States in this period would likely have had a different political message and tone from this cartoon.

Explore various methodologies from the many fields in which the history of cartoons is utilised. Think about how different fields approach cartoons and how their conclusions differ from one another for a broader understanding of the many uses for cartoons as primary sources.

Further Resources

Bigi, Alessandro, Kirk Plangger, Michelle Bonera, and Colin L. Campbell. “When Satire is Serious: How Political Cartoons Impact a Country’s Brand.” Journal of Public Affairs 11, no. 3 (2011): 148–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.403.

Buhle, Paul. “History and Comics.” Reviews in American History 35, no. 2 (2007): 315–23. https://doi.org/10.1353/rah.2007.0026.

Gordon, Ian. Comic Strips and Consumer Culture 1890–1945. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Ndalianis, Angela. “Why Comics Studies?” Cinema Journal 50, no. 3 (2011): 113–17. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2011.0027.

Bibliography

Carl, LeRoy M. “Political Cartoons: ‘Ink Blots’ of the Editorial Page.” The Journal of Popular Culture 4, no. 1 (1970): 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.1970.0401_39.x

Caswell, Lucy Shelton. “Drawing Swords: War in American Editorial Cartoons.” American Journalism 21, no. 2 (2004): 13–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08821127.2004.10677580

Chen, Khin-Wee., Robert Phiddian, and Ronald Stewart. “Towards a Discipline of Political Cartoon Studies: Mapping the Field.” In Satire and Politics: The Interplay of Heritage and Practice, edited by Jessica Milner Davis, 125–62. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Collins, Kathleen, and Ann Wilsher. “Petticoat Politics: The Capture of Jefferson Davis.” History of Photography 8, no. 3 (1984): 237–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/03087298.1984.10442228

Cuff, Roger Penn. “The American Editorial Cartoon-A Critical Historical Sketch.” The Journal of Educational Sociology 19, no. 2 (1945): 87–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/2263389

Davis, Jefferson. The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. 2 vols. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1881.

Howard, Sheena C., and Ronald L. Jackson. Black Comics: Politics of Race and Representation. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Kemnitz, Thomas Milton. “The Cartoon as a Historical Source.” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 4, no. 1 (1973): 81–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/202359

Library of Congress Online Catalog. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.loc.gov.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Online Catalog. Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/pictures.

Rowland, Eron. Varina Howell: Wife of Jefferson Davis. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing, 1927.

Silber, Nina. “Davis, Jefferson, Capture Of.” In The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, edited by Charles Reagan Wilson, Nancy Bercaw, and Ted Ownby, 308–10. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009. https://www.jstor.org/stable/.

Stearns, P. N.. “Social History Present and Future.” Journal of Social History 37, no. 1 (2003): 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2003.0160

Welcker, F. “Jeff’s Last Skedaddle, c. 1865, Library of Congress Catalog.” Accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661833/.

Yaszek, Lisa. “'Them Damn Pictures: Americanization and the Comic Strip in the Progressive Era.” Journal of American Studies 28, no. 1 (1994): 23–38. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875800026542

Notes

Caswell, “Drawing Swords: War in American Editorial Cartoons.”

Roger Cuff’s definition of an editorial cartoon for academic purposes varies from the cartoonist industry definition of cartoons specifically published in an editorial column of a newspaper or print publication: ‘Published drawings that are designed to produce a humorous effect and to teach a lesson are editorial cartoons. When a cartoonist creates a sketch that is both pictorial and editorial, he communicates an opinion or a conviction. He reveals a preference for, or a judgment against, some person or class or issue or foible. Both social and political cartoons have been used as editorial vehicle’. Cuff, “The American Editorial Cartoon--A Critical Historical Sketch.”

Stearns, “Social History Present and Future.”

Chen et al., “Towards a Discipline of Political Cartoon Studies,” 125–62.

Chen et al., “Towards a Discipline of Political Cartoon Studies.”

Collins and Wilsher, “Petticoat Politics: The Capture of Jefferson Davis.”

Silber, “Davis, Jefferson, Capture Of,” 309, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9781469616728_bercaw.86.

Collins and Wilsher, “Petticoat Politics,” 239.

Silber, “Davis, Jefferson, Capture Of,” 310.

Davis, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, 742.

Carl, “Political Cartoons: ‘Ink Blots’ of the Editorial Page.”

Lisa Yaszek quotes William Marcy Tweed from 1871 on the potency of cartoons for illiterate audiences when he stated, ‘Stop them damn pictures. I don't care so much what the papers write about me - my constituents can't read. But dammit, they can see pictures’. Yaszek, ‘ “Them Damn Pictures”: Americanization and the Comic Strip in the Progressive Era.’

For a comprehensive breakdown of the many methodological approaches per discipline, see Chen et al., “Towards a Discipline of Political Cartoon Studies: Mapping the Field,”, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56774-7_5.

All underlining and punctuation are in accordance with the original cartoon.

Rowland, Varina Howell: Wife of Jefferson Davis, 406–09.

‘Wanted – Agents Advertisement from Chicago Tribune’, April 20, 1865. From Library of Congress Online Catalogue, accessed February 18, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn82014064/1865-04-20/ed-1/?sp=4; “Wanted – Agents Advertisement from Chicago Tribune,” September 22, 1865. From Library of Congress Online Catalogue, accessed February 18, 2021, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn82014064/1865-09-22/ed-1/?sp=4.

Collins and Wilsher, 239.

F. Welcker. ‘Jeff’s Last Skedaddle’, c. 1865, Library of Congress Catalog, accessed February 8, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661833/

Silber, 310.

Collins and Wilsher, 243.